… and you can enter as many times as you like!

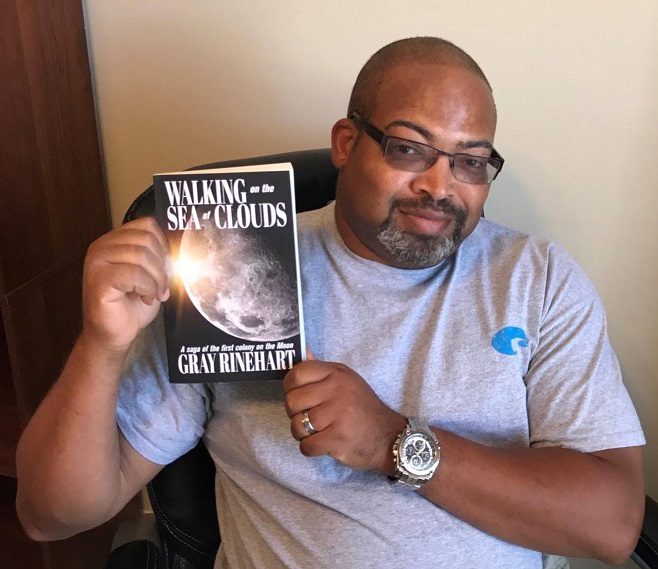

As announced previously, the Walking on the Sea of Clouds audiobook is complete and available for your listening pleasure direct from Audible or, if you prefer, from Amazon — and between now and Tax Day, we’re going to hold multiple drawings to give away free Audible downloads for it!

Why Tax Day? Because somebody ought to get some good news on that day!

Why multiple giveaways? Because anything worth doing is worth doing more than once! (And because the good folks at Wordfire Press gave me several download codes to do with as I pleased, so I’m giving a bunch away.)

How do you enter? Just sign up for my newsletter using this special link, and then every time you share the link and tag me, I’ll enter you in the drawing again!

(Image from Wikimedia Commons.)

If you’re not quite sure whether Walking on the Sea of Clouds is your kind story, here’s what some folks had to say about it:

- This book will be treasured by anyone who has ever dreamt of visiting the Moon, walking on another world, or bathing beneath the light of a distant star.

–David Farland - If you’ve ever wanted to be a colonist on the moon, this is as close as you will ever get without going there yourself.

—Abyss & Apex - … as entertaining as some of Heinlein’s early fiction, …. closer to the type of fiction Jerry Pournelle wrote in the 1960s and 1970s…. captures a pioneering era that once was and could be again.

—Ad Astra - Much like The Martian, Walking on the Sea of Clouds puts you on a lifeless rock and makes you think about why we explore new frontiers even as it explains how it can be done.

—Booklist - Everything about Walking on the Sea of Clouds feels amazingly authentic.

–Edmund R. Schubert - Annoyed you haven’t been to the Moon yet? Then pick up Walking on the Sea of Clouds; you’ll feel like you’re there.

–Charles E. Gannon - This is meat and potatoes for the hard science fiction fan.

–Martin L. Shoemaker

It’s a near-future story of survival and sacrifice during the very early days of a lunar colony, and explores the reasons why people sign up for such daring enterprises and the price they’re willing to pay to help them succeed. In addition to Audible, you can also find it in other formats on Amazon and other online sources including Baen e-books.

I hope you’ll give it a listen (or a read), and let me know what you think!