That title may be a bit uncharitable, because history surely is full of people accomplishing great things, making monumental discoveries, and generally advancing the human race from savagery to civilization. History is also, unfortunately, rife with examples of people being terrible to one another.

Some of that “being terrible” began as “being natural,” because the natural world is a frightful place — the phrase “red in tooth and claw” is literally the natural state of things for most creatures on the planet. Seriously, that’s why our ancestors worked so hard to rise out of savagery and to tame the world around them.

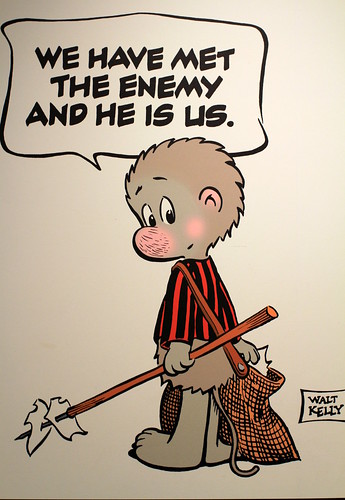

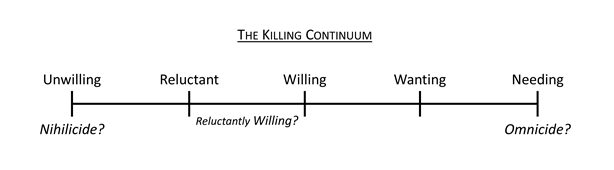

By the time Ogg the caveman decided to brain his fellow caveman Uldarr with a rock because he wanted Uldarr’s share (or Uldarr had stolen Ogg’s share) of the wooly mammoth they’d killed, their ancestors had scratched and clawed — literally clawed, in the days before tools — their way up to a point of some sophistication compared to where the human race started. Fast forward to any point in history, anywhere on Earth, and you’ll see the same things: scarce resources driving people to eliminate rivals; slights and insults provoking people to wrath; and personal conflicts growing into family feuds, tribal battles, and even global wars. Aggravation, escalation, devastation.

Because of all that shared history, and the animosity that pervades human life and culture, it’s a wonder we get along with as many people as we do, as well as we do. Here in the U.S., a lot of that shared history has to do with race, and racial tension is one of the most persistent and pernicious ways these conflicts have manifested.

What, then, does history offer to help us?

History tells us a great deal about what happened in the past: who did what, how they did it, when and where it took place, the kinds of things we can document and present as facts. Some aspects may be disputed, from major elements of events to minor details, and subsequent research may turn up new facts that change our understanding of what happened.

Why things happened, however, and especially why the people involved did the things they did, can be a lot harder to determine.

(Image: “History wallpaper/desktop image,” by Eric Turner, on Wikimedia Commons.)

Why something happened in history may seem evident, in the way that why a hurricane forms is evidently because an area of low pressure developed over warm ocean water; but the cause(s) we ascribe to human events may be too simplistic and may not tell the whole story. Why an historical event happened the way it did is more akin to figuring out why a particular hurricane hit a particular place on a particular date — or, to use a more erratic weather metaphor, to postulate why a tornado (perhaps spawned by a hurricane) destroyed one house and left the house next to it undamaged. It’s much more difficult to explain, and the reasons we come up with are usually not as precise as we would wish. And because such things are erratic, the reasons we put forth don’t lead us to being able to predict future “storms” with great precision.

Unlike hurricanes and tornados, of course, sometimes the people involved in historical events leave records — diaries, reports, memoirs; letters, articles, perhaps blog posts these days — which are subject to scrutiny and interpretation. But those records can be considered tainted by inaccurate observation or unclear memory, or even corrupted by agenda or ideology or passion. All of which combines to make historical analysis difficult, and history-based speculation sometimes unreliable.

Therefore, history is not on our side. It does not offer us a trustworthy guide to the future, and the marks it’s left on the present are often indelible and ugly.

But we don’t need history to be on our side. In fact, having now written all this, it seems silly to think it ever would be. To say that history could be on our side is like the terribly imprecise saying from a few decades ago, “Information wants to be free.” It’s nonsense. Information doesn’t want anything — it is noncorporeal, and has no needs or desires to satisfy. Some people want information to be free, but that’s another matter.

Likewise, some people want history to be on our (i.e., their) side, but that’s another matter.

History isn’t on anybody’s side, and the most we can hope for is that our historical record is as complete and accurate, as accessible and permanent, as possible. Because if we let aggravation lead to escalation and then to devastation, if we find ourselves in a broken society (hopefully not reduced as far as Ogg the caveman’s), it would be good to be able to relearn whatever lessons we can from history, in hopes of not repeating too many of the same mistakes.

But, what do you think?