Over at the redesigned Baen Books* web site, they’re running features by Baen authors — a short story one time, a short article the next — and the recent article “The Size of It All” by Les Johnson is fantastic. Here’s the opening (with emphasis added):

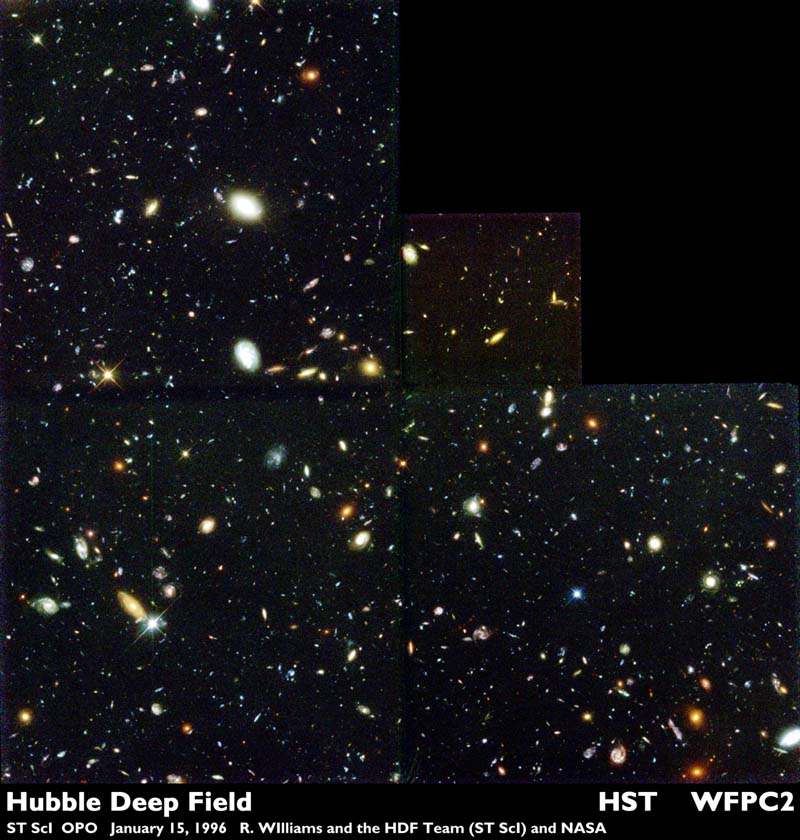

For ten days in 1995, the Hubble Space Telescope pointed its mirror to a small patch of seemingly empty sky near the Big Dipper and started collecting light. (“Seemingly empty” means that no stars or galaxies were at that time known to be in that particular piece of the sky.) The part of the sky being imaged was no larger than the apparent size of a tennis ball viewed from across a football field. It was a very small portion of the sky. What they found was awe-inspiring. Within that small patch of nothingness was far more than nothing. The image revealed about three thousand previously unseen galaxies, creating one of the most famous of Hubble’s images and my personal favorite. The sky is not only full of stars but also of galaxies and they are very, very far away.

Here’s the mosaic image the telescope produced:

(Hubble Deep Field. NASA image.)

Since that image was taken, the Hubble Space Telescope has produced the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, which revealed ten thousand previously unseen galaxies, even farther away and further back in time, in another “seemingly empty” part of the sky.

It’s apparent that we are nearly insignificant specks in the grand scheme of the universe, and if you read “The Size of It All” you’ll get an idea of just how small our world — indeed, our entire little part of the celestial sphere — is. The question of how big the universe really is always puts me in mind of one of my favorite Chris Rice songs, “Big Enough”**:

When I imagine the size of the universe

And I wonder what’s out past the edges

And I discover inside me a space as big

And believe that I’m meant to be filled up with more than just questions …

Sometimes I feel overwhelmed by it all. It’s on those days that I rely most on faith to keep me going.

___

* FULL DISCLOSURE: I’m affiliated with Baen as their “Slushmaster General.”

** Copyright Clumsy Fly Music. Used without permission, but in good faith so hopefully they won’t send their lawyers after me.