I am not an epidemiologist, nor am I a medical person. I am, however, experienced with risk assessment and analyzing risks from my days as the Deputy Director of Safety and Health, and the Systems Safety Program Manager, at the Air Force Astronautics (nee Rocket Propulsion) Laboratory at Edwards AFB, California.

In the field of rocketry, dealing with toxic propellants of various kinds as well as massive amounts of flammable and explosive materials, risk assessment is serious business. We strove to understand the risks associated with our operations and to mitigate them as much as possible.

In the years since I left the Rocket Lab — I will always think of it as the Rocket Lab, “the Rock,” no matter how many times they change the name — I’ve had ample opportunities to analyze risk in other contexts. Today, let’s consider the SARS-CoV-2 virus, frequently called the “coronavirus” even though it’s really one of many such viruses.

Risk, in general, may be thought of as a combination of the potential for a bad thing happening and how bad the results are expected to be. In rocketry, we characterized it as probability times severity. For instance, an event that would damage an expensive piece of equipment would generally be considered less severe than an event that would injure a person, but the overall risk to the project might be similar if the first, damaging event was much more likely to happen compared to the second, injurious event. In each case, we analyzed the risks in order to figure out where we might apply physical and procedural measures to reduce it.

The risk presented by the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a little different because the severity of the COVID-19 disease is a given. Still, it seems to me we can conceptualize the risk in useful ways by assessing the probability of developing the disease and even that of catching the virus.

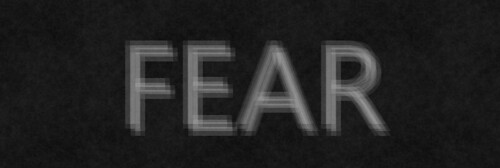

First, using reports that mortality associated with COVID-19 seems to be related to patients’ ages and whether they suffered from ill health, I took a stab at a matrix showing the risk of dying from COVID-19. Assuming one has actually been infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, it seems reasonable to say the risk of dying from COVID-19 rises with age and the number of complicating factors, as shown:

(Estimated risk of dying from COVID-19, having contracted the SARS-CoV-2 virus.)

Thus, as the doctors and epidemiologists have said, the older we are and the more health problems we have, the higher our risk and the more diligent we should be in protecting ourselves. Makes sense to me.

But what’s the risk of actually contracting the SARS-CoV-2 virus?

That’s a more complicated issue. Certainly one must be exposed to the virus, but every exposure does not result in infection. And every exposure is not the same.

For instance, the emphasis on Proximity Avoidance (my preferred term for “social distancing”) neglects how long we are in close proximity to one another. I have seen people step off the sidewalk into a thoroughfare in order to avoid spending a second or two within the recommended six-foot distance, because they apparently believe that the briefest encounter will result in infection. I’ve also read complaints about the practice of holding doors open, for the same reason.

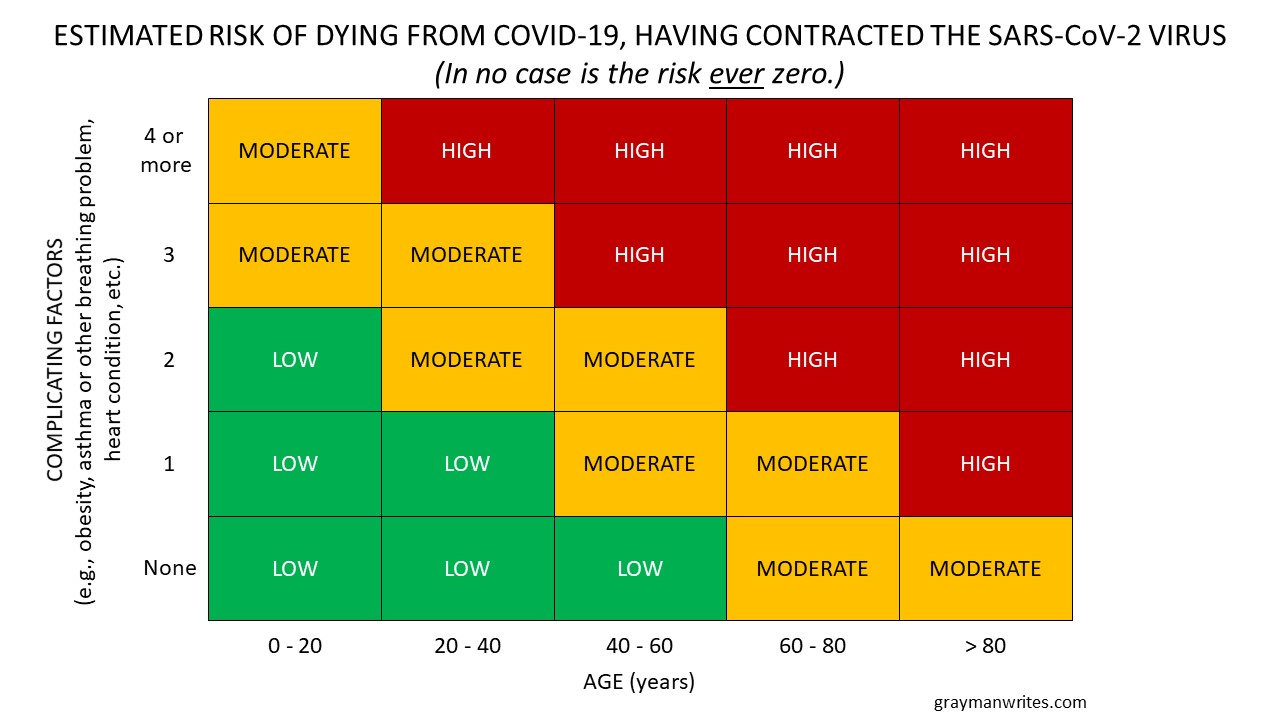

Realistically, however, the risk is not just a function of distance but also of time. Spending a few seconds passing someone on the sidewalk is not as risky as standing shoulder-to-shoulder with them for several minutes. So if we assume someone near us is carrying SARS-CoV-2 and neither of us is wearing a mask, the risk of contracting the virus from them based on both distance and time probably looks something like this:

(Estimated risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 virus from encountering a single carrier.)

Other factors could come into play, of course. Passing in a tight hallway is likely a bit more risky than passing on a greenway. And if at least one of us is wearing a decent (i.e., fluid resistant) mask, most of those blocks marked “high” probably fall to “moderate” risk levels.

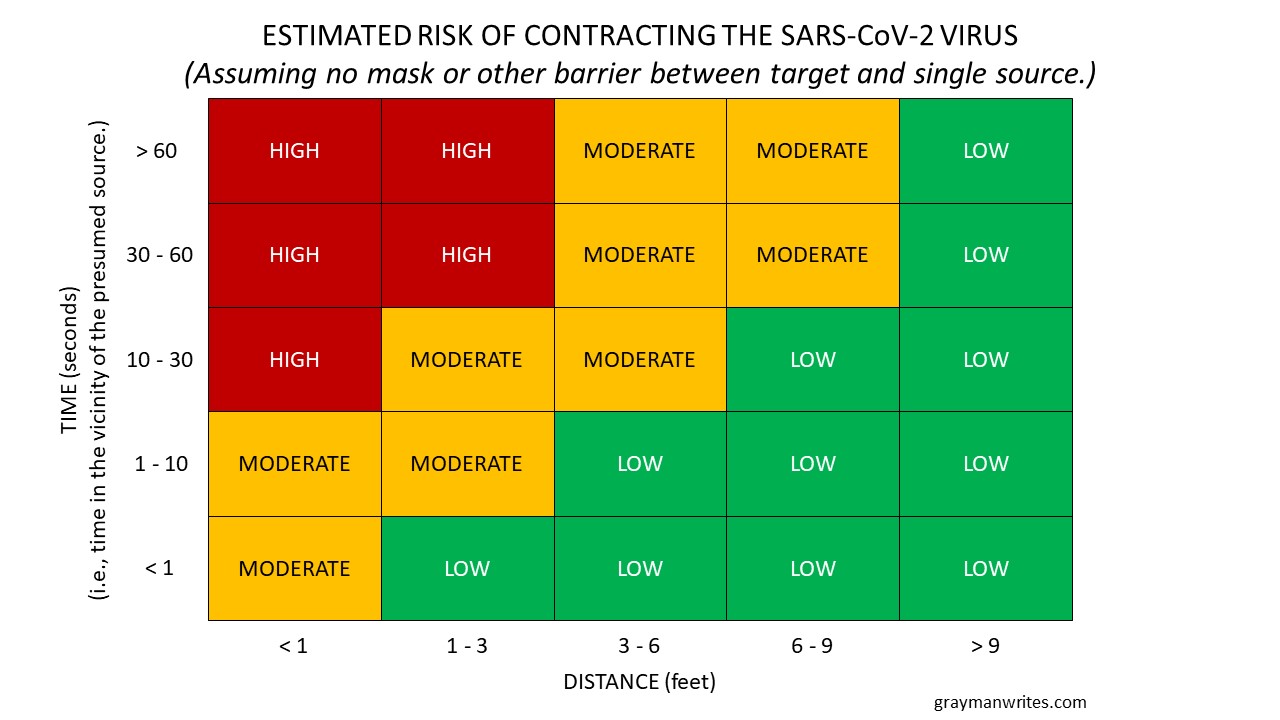

As we move away from one-on-one encounters to the possibility of encountering groups of people, the risk picture becomes more complicated and harder to illustrate in a simple matrix format. Both time and distance remain factors in how risky it is to be around people, and if we add to them the numbers of people and whether they are masked, we need to simplify things a bit in order to account for so many factors. The assumptions remain:

- The closer we are to a carrier, the higher the probability of transmission

- The longer we spend in the vicinity of a carrier, the higher the probability of transmission

- The more people nearby, the higher the probability that one is a carrier

- Masks that catch droplets reduce the risk but do not eliminate it

We can combine time and distance by dividing the duration by the amount of separation. Thus, the longer we spend in close proximity with someone, the higher the value. As shown in the matrix above, spending a full minute six feet away from someone is probably about the same risk as spending ten seconds only one foot away from them.

We can also combine the group size and masks (or “barriers”) factors. In this case, we can divide the number of carriers (or presumed carriers) we encounter by how many are wearing masks — and whether we are wearing one. So if we are masked and encounter a single person wearing a mask, the “carrier/barrier” factor would be one presumed carrier divided by two barriers: 1/2, or 0.5. Likewise, if we encounter four presumed carriers at once and only one of them (plus us) are masked, the factor would be 4/2, or 2.0. The higher the value, the higher the probability of exposure.

Putting those factors together gives a risk estimation that looks something like this:

(Expanded estimation of risk of contracting the SARS-CoV-2 virus.)

Folks may quibble about the values I chose for each axis, or whether a particular intersection should be rated differently (e.g., as “moderate” instead of “low”), but the real question after all of this is, how much risk are you willing to accept?

And the question after that is, should you force anyone else to accept a higher or lower risk than they are willing to accept?

In my last blog post, “Home of the Scared,” I noted that the fears associated with the SARS-CoV-2 virus are not new. “Fear was already rampant in our risk-averse society, albeit at something of a maintenance level, in terms of how tentative many people have become in their day-to-day lives. But people with vested interests applied the scary virus as if it were gasoline to more general fears that have smoldered for years.” It’s been all too easy to inflame those fears, because neither the media nor the recognized experts have presented this in risk management terms. Rather, many commentators and observers have emphasized the dangers of COVID-19 — i.e., its severity — rather than the probability of contracting it, to the point that “… a moderate danger like SARS-CoV-2 has brought some people to the point of near panic.”

Now, even though it’s been shown that moderate risk-taking results in greater satisfaction with life, neither fearlessness nor recklessness are especial virtues. Fear in itself is not a bad thing, nor is it a negative trait: It’s a natural reaction to extant threats. But while the inability to sense a threat is a deficit, and refusing to acknowledge a threat is foolish, it’s better to consider threats realistically and to take reasonable steps to reduce their risk — all the while accepting the simple fact that life without risk is impossible.

___

P.S. Don’t forget to order your Proximity Avoidance T-Shirt….

(Proximity Avoidance logo, designed by Christopher Rinehart.)