Forty years ago this week, the Soviet Union was in the midst of launching the first two spacecraft of a four-vehicle mission to the red planet. Each was launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome on a Proton booster.

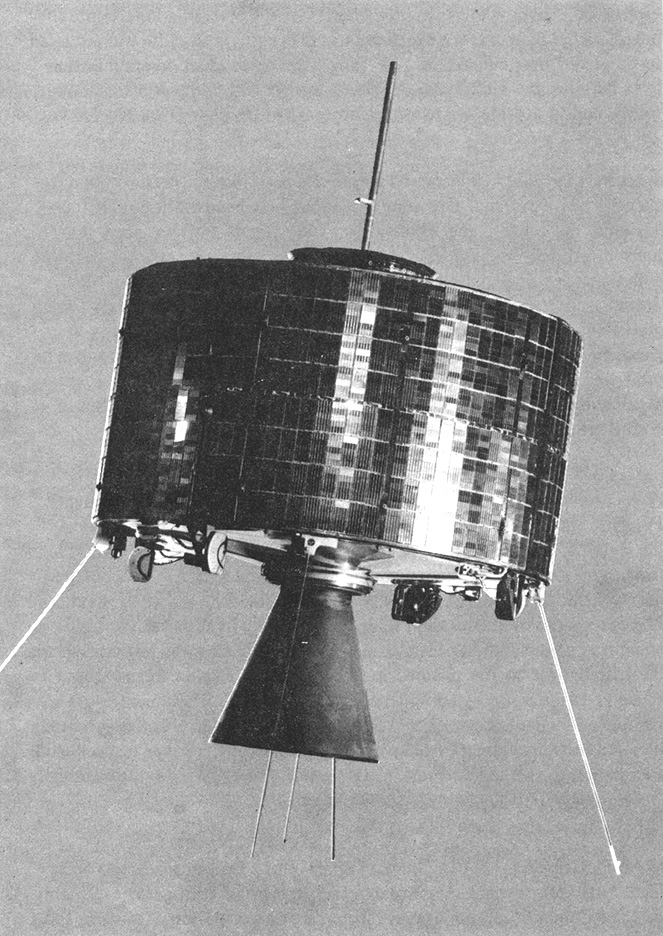

(Mars 4. Image from the National Space Science Data Center.)

The first of the spacecraft, Mars 4, was launched on July 21, 1973 — so 40 years ago today, it was on its way. Unfortunately, it was unable to enter orbit when it got to Mars.

It was put into Earth orbit by a Proton SL-12/D-1-e booster and launched from its orbital platform roughly an hour and a half later on a Mars trajectory. A mid-course correction burn was made on 30 July 1973. It reached Mars on 10 February 1974. Due to a flaw in the computer chip which resulted in degradation of the chip during the voyage to Mars, the retro-rockets never fired to slow the craft into Mars orbit, and Mars 4 flew by the planet at a range of 2200 km. It returned one swath of pictures and some radio occultation data which constituted the first detection of the nightside ionosphere on Mars. It continued to return interplanetary data from solar orbit after the flyby.

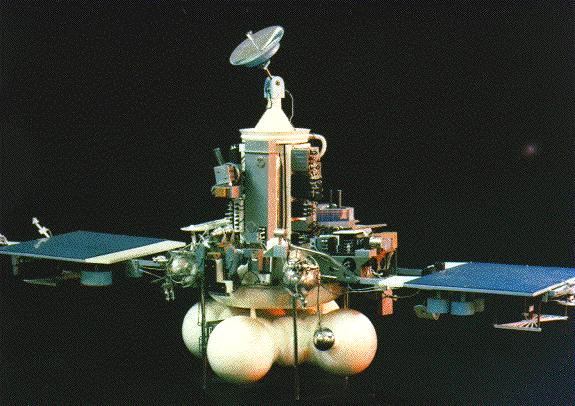

The first of its companion spacecraft, Mars 5, was launched on July 25, 1973 — so 40 years ago today it and its Proton booster were undergoing final preparations for launch. Mars 5 successfully achieved Martian orbit, but operated for only a short time.

After a mid-course correction burn on 3 August, the spacecraft reached Mars on 12 February 1974 at 15:45 UT and was inserted into an elliptical 1755 km x 32,555 km, 24 hr, 53 min. orbit with an inclination of 35.3 degrees. Mars 5 collected data for 22 orbits until a loss of pressurization in the transmitter housing ended the mission. About 60 images were returned over a nine day period showing swaths of the area south of Valles Marineris, from 5 N, 330 W to 20 S, 130 W. Measurements by other instruments were made near periapsis along 7 adjacent arcs in this same region.

The next two missions, Mars 6 and 7, would be launched on August 5th and 9th, respectively. The loss of Mars 5 would make their operations harder, as it had been “designed to act as a communications link to the Mars 6 and 7 landers.”

Despite their ultimate failures, the series of launches themselves were quite an achievement: preparing and launching two big boosters one right after the other, and then doing it again two weeks later. One of the most interesting experiences of my Air Force career was getting to observe the initial stages — primarily mating the spacecraft to the launch vehicle — of a Proton launch campaign at Baikonur. Having seen what goes into a single launch, that they launched four payloads in such a short time is very impressive.

by

by