I had the idea, probably months ago now, and set it down in my long list of strange, passing thoughts, for something called the Freedom Gauge, or Freedom Meter. I think that might be helpful in making political decisions and informing political opinions.

Why? Because, at root, every government restricts citizens’ freedoms in some way(s) — after all, we accept certain limitations on complete, anarchic freedom as part of the social compact — and every law that is passed curtails some freedom(s). The question is, how much?

My first thought was that of being a watchdog over legislatures so that, in the process of new laws being proposed, debated, and enacted, the bills’ effects on personal freedom might be shown on the Freedom Gauge. Different legislative proposals could be compared in terms of their “Freedom Quotient” or something. The idea was to present in graphical form how much particular legislation would curtail freedoms. (And, in a flight of the wildest rose-colored-glasses fancy, I thought legislatures themselves might make use of the gauge to show how little impact their proposals would have on the average citizen.)

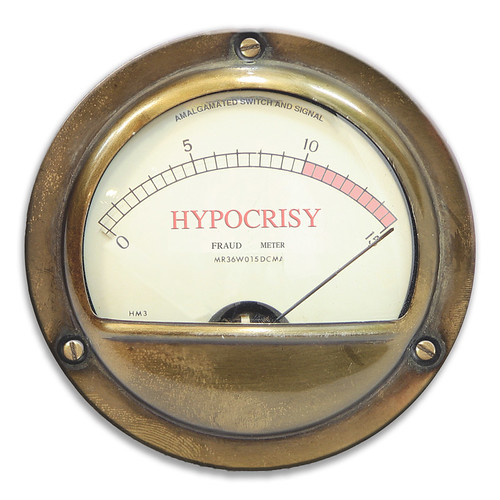

Yes, something like that … (Image: “Hypocrisy Meter, Pegged,” by Kaz Vorpal, on Flickr under Creative Commons.)

My second thought was an international comparison of some sort: a monitor of the freedom(s) afforded — or denied — by different countries. Basic data might come from the CIA World Factbook or other trustworthy sources, and might include socioeconomic figures, crime statistics, human rights abuse reports, and whatnot. But I think the local version, the what-law-are-they-passing-today version, may be more useful.

If I had the wherewithal — the time, money, and know-how — I think I would register a website called “freedomgauge.com” or “freedom-meter.com” (both domains were available as of noon today) and build a site that would “measure” — somehow — and report infringements on freedoms: infringements in existence now, and ones that are being proposed. Alas, that seems like a monumental task. I suppose it would have to be crowd-sourced in some way, reliant on contributors the way online encyclopedias are. And that’s far beyond my level of expertise.

So, no, I don’t see myself making a “Freedom Gauge” happen, though I think it might be a good thing.

With that said: if you think the idea has merit, feel free to run with it and see what you can do!